Scaled snake oil

Agile is about culture and possibly about cultural change. Scaling agile means, radically, to scale cultural change. This is an incredibly difficult thing to do. Peter Drucker coined the phrase

Culture eats strategy for breakfast.

You better prepare for the long run. Is it clear, why you want to change? You are: managers, who define how the system works, product managers, who determine what kind of product to build, research and development people, who explore possibilities, engineers, who make the product, salesforce, who will drive sales, project managers, who are in charge of leading one-of-a-kind endeavors – you will identify even more people and roles for your organization.

Do your leaders have a sense of urgency that agile is the way to go? Can they argue why agile makes sense, and will they? Do your leaders know what problem they want to solve by being agile?

You have to change, you know that, because the first rule of life is

Adapt or die.

Do you think it can happen by implementing a new release train process that you have read about in the latest scaled agile book? By disseminating a slide deck to your subordinates, giving the order to work in Sprints and counting Sprints as unsuccessful if tasks are left undone at the end of the Sprint? By letting the Project Management Office give instructions to standardize Scrum Boards in the entire company with predefined columns? By printing sticky note templates to have them all look the same on the boards, without referring to your workforce? These top-down communications are patterns of how to probably get agile wrong. If you think this is scaled agile and will lead to cultural change, then you are heading for scaled snake oil. Mentally, your people will step aside and identify the entire thing as theater communication.

Agile is not implementing a process and then follow. Agile has to be earned, not given.

Every organization is unique

Every organization has to find answers to questions like What delivers value?

, What is a success?

, How would we know we achieved success?

, and, of course, Why to be agile?

, and How would agile help us?

Agile properties

Find out, if this is something for you: Center around people and results, not around processes. Processes are servant, not master. Still, continuously improve processes and focus less on improving the monitoring of people. Identify what brings value to your customers and organize around delivering that value. Money is not the goal; it is a result which comes from achieving value for delighted customers. Have a straight line from your product strategy to your release strategy to the delivery order of the features within a release. Things are ordered in a way to deliver the highest value first, in small increments, regularly. Your people are oriented about that and understand. Transparency on all levels with everyone seeing the same figures, whether it´s the progress of value delivery or costs and earnings. The workforce is emancipated and authority is brought to where information lives and not information is brought via monitoring chains to "authorities." Give control to people and not take control. Decentralize and find ways to let information and energy flow smoothly to the places where needed. Be clear about the goals and intent, but leave space for the workforce to find ways how to achieve the goals. Grow competency to perform.

Strive for a learning attitude on all levels to enable the organization to get better, and to lead change. Team growth and personal growth are not only lip service and to be a leader is about duties and responsibilities and not necessarily about privileges. Leaders are cultivators rather than controllers [Mayer 2013:63]. Instead of one-way, top-down commanding communication, the horizontal discursive approach is the default. Top-down is only used where needed. This organization is more of a leader-leader type instead of playing the leader-follower game (compare with [Marquet 2013]). You want leaders on all levels and not people with their brains off and only following given procedures.

The agile organization is a failure resilient, success-seeking, cooperative, status-quo challenging, potential-growing, knowledge worker organization. It is not a failure-avoiding, routined-good-behavior, following-procedures company.

Not for mummy´s boys

You may want to use agile only for a single project with 8, 20 or even 50 people and don´t think about your entire organization at first hand. That is okay, growing natural makes sense, and to understand how things work in the small and then scale up, will give a chance for any scaling endeavor to function. Chances are, you try to go the agile way because your current project is about to sink, or your engineered waterfall projects fail too often. This motivation may be of help because then you have some pressure for clarity and the right decisions – but you do not have the guarantee that you will make the right decisions, of course.

Being agile in a team of 8 people is incredibly difficult if you haven´t done it before. It is likely the most disciplined way of working you ever had to, or, better, wanted to achieve in your work life. It is not easy going. You have to be unafraid and explore. But it is not all hard stuff, it is mostly about people and purpose and real collaboration, about engagement, choice, and fun at work, about trust, freedom, ownership and a sense of self [Mayer 2013:29]. I suppose no one ever achieved something great only because it was told them to do. You can achieve great if you see a purpose, when you are convinced, when you reinforce the spirit of your team, by making and learning, making and learning. As managers, you cannot buy such behavior and attitude, nor can you give orders to do so. You have to set suitable constraints to give self-organizational forces a direction and give people the authority to act like human beings. Be prepared to learn and adapt, because you will have to.

That said, why would you want to do that? Isn´t it better for the organization to be robust, reduce room for surprise and have people following orders?

I can identify four angles to assess the topic: the market, the problem class, the process model and the people.

Market

The following paragraphs on market have been taken from the text The art in our work.

The centralized planning, disassembly, and automation of work brought us to the integration of human labor into precise production timing and to an understanding of companies as automatic production machines. Wohland and Wiemeyer explain the concept with their model of the Taylor-Tub.

In the Taylor-Tub the articles of the individual are not of importance, because all workflows, procedures, and processes are defined upfront and have to be followed. This makes the system robust, but inflexible. We have been educated for this world of working, which means we have been taught to follow. This brought up disruptive productivity growth and inert mass markets during the last century. The biggest problem to solve for these markets was: how to produce as much as possible at the lowest price.

Today's markets are more and more characterized by their narrowness and/or complexity. This complexity requires a better understanding of customer needs, higher flexibility and often interdisciplinary approaches. Those companies that can create and live up to such dynamics, the top performers, set the less capable companies under pressure. The biggest problem to solve for these markets are: how to connect with the customer, identify what delivers real value and be able to do it fast. Companies that cannot create such dynamics will suffer the pressure.

The necessary momentum is being created by dynamic people, by experienced and skilled workers who responsibly and self-organizing produce results – people who can bear with complexity. For those people, values and leadership are of much higher importance than centralized control and management.

Agile values support dynamic and skilled knowledge workers. For your organization to be able to cope with current market requirements, you may be forced into an agile working style, whether you like it or not.

Problem class

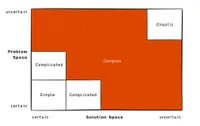

Any innovative endeavor will challenge knowledge workers with uncertainty about the problem space and the suitable solution space. To pick up a slightly modified Stacey Matrix, it is this uncertain complexity space where knowledge workers are at home, and that´s where agile is positioned.

In this complex area, we talk about dynamic, self-organizing systems with non-linear behavior – an environment, where more is unknown than known. The apriori definition of all states of which the system can be in – and how to move the system from any of these states into a desired other state – is not possible. One has to work through this environment to get a grip on it (you can only learn to ride a bicycle by doing it, not by reading about it). Therefore the apriori definition of a detailed step-by-step execution process will not function, and to put more effort into upfront planning will only consume more energy but won´t improve the outcome.

This leads to the next, tightly coupled angle on the agile topic: the process model to use.

Process model

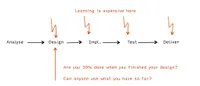

Being positioned in dynamic, competitive markets that are characterized by uncertainty of both, problem space and solution space, we have to ask for a suitable process model to support and guide the workforce to achieve results. The detailed upfront planning of execution steps, the defined process model, does not bring any advantage, instead even the disadvantage of false safety and effort consumption. The waterfall process follows such a defined process model.

Consider the following questions:

- You already spent 30% of your available time and effort and just finished your design phase. Are you 30% done? Probably you can´t tell, because you are sitting on a stack of unvalidated paper. No working code.

- Do you have something of value for your customer or yourself? Can your customer do something with your paperwork? I assume not, again, only a stack of unvalidated paper. Reality will correct that when you start to write working code.

- Let´s say you learn during your implementation phase and something has to be reworked which makes a design change necessary. Will you proceed a change request? How long will you try to avoid it? Usually, a change request in the waterfall process is treated like a failure which is being sought to circumvent as long as possible. That´s why change requests are so expensive in this process model. And that´s why learning is so costly in the waterfall process.

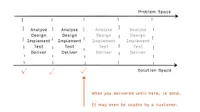

In the agile world, we respond with the empirical process model.

Working in short iterations of 1, 2, 3 or 4 weeks and delivering working software at the end of each iteration will give you the security net that is comparable to what mountain climbers do when they climb and secure, climb and secure. At the end of each iteration, you reach a safety point that tells you what is and what not.

Picking up the same questions I already asked for the defined process model:

- If you have spent 30% of your time and effort, you can accurately compare that with the list of already done pieces of software. Your measurement for progress is no longer spent effort or time, but done work compared to missing pieces yet waiting to be delivered. This is clear and simple. Possibly you are 30% done at that point. Your customer decides, and you can tell him exactly what is done.

- Do you have something of value for your customer or yourself? You should. If you built working software in each iteration, even if not delivered to the customer, you have something to show and to learn from and to rely on.

- Now you learned something after 30% of your effort is spent (of course, you did learn even before). Can you change direction quickly? Probably, because after each iteration you can decide what the next most important move is and go ahead while delivering software. And I have two additional questions:

- Is it difficult to work this way? Of course. The team has to master the culture shift to deliver done software by following the value and completing the work that brings the most value first. Also, the technical skills of the team have to grow to support this agility. Without automatic tests and automatic build of software in short intervals, you won´t get there. All your systems need to be aligned towards giving feedback as fast as possible.

- Will this way of working help you to deliver appropriate results? Sure. Feedback and learning are an inherent part of this model. This responds directly to the uncertainty of the complex problem class that you are in. To deal with a world where more is unknown than known requires us to "cut through the noise by taking action" [Beedle and Schwaber 2002:27] and continuously validate our mental models against reality – as we go.

People

In this short enumeration from the market over problem class to the process model, the last mentioned is the people. Last, not least. People are the most important. Everyone counts, it is no longer that people are being told what to do and follow. With the follower mental model you will not survive in dynamic, competitive markets, nor in complex problem situations.

The only way to survive is with dynamic leaders at all levels in the organization; people who explore problem and solution spaces and find ways to achieve things, artists, status-quo-challengers with excellent skills. These people have the drive to achieve and strive for purpose, autonomy, and mastery. Of course, in job advertisements, all companies seek for this kind of folks, but after the hiring process, in the real life

, these talents are being treated like if they were all the same and interchangeable, average, like resources, often without any sense and respect. To make it clear, the agile mindset asks for creativity, attitude, know-how, opinions, and cooperation. We want people in their entireness and give them space to grow. We want them to ask why

and insisting on answers. I believe, everyone in current corporate structures has the ability and the wish to act as a whole human being, but when people are treated day-in and day-out as interchangeable resources, it doesn´t take long, and they behave accordingly, switch brains off and do something interesting in their spare time. You know – setting constraints directs self-organization!

To sum it up, agile does help in competitive dynamic markets. It does help to solve complex problems by leveraging an empirical process model and reinforcing the self-awareness of people as whole human beings.

Programmers drive it

The agile movement started in the IT industry. It is driven by programmers and engineers at first hand, by people who are in the process of making and delivering. That kind of people who know since long how hard it is to get an idea to life and build something which other people like to use (and pay for). I assume the agile mindset found its first expression in Extreme Programming and Scrum in the second half of the 1990s, followed by the Agile Manifesto in 2001. And to me, when talking about agile in terms of frameworks, still I mean Scrum XP, I don´t see we need more.

The ideas, values, and principles of agile are pro people and pro results. The central working unit is the team, at max ten people, cross-functional and being able to deliver results. The team is emancipated, has authority to decide, the competency to act, and clarity in the goals to achieve.

Agile is about letting people make things that deliver value now, while being connected to their work and validating results. The people are value-focused and have the technical expertise to deliver frequently.

Agile delivery goes with the least possible process that is expected to function. This process is a servant, not a master. For example, the Scrum framework can be drawn and explained on a beer coaster – which does not mean it´s easy to live up to.

If you have not achieved this way of working for a single team in your organization, why would you believe you can overstep this level and try to work agile within the entire organization, in multiple locations, continents, timezones, cultures?

Transparency

You don´t solve problems by making them harder to see. You have to use the fast failure that is being promoted by agile instead of hiding it under an additional process layer. A thing like SAFe (Scaled Agile Framework) will put such layer between the delivery folks and the management. It allows the management to ignore change and see the world as they have always seen it – only with a different decoration. And yet (or because of), there is a market for this kind of stuff. SAFe is not alone, to get an impression I´d like to point you to this article by Ron Jeffries. The LAFABLE process, which Mike Cohn introduced on the 1st of April 2014, is making a joke of scaling frameworks.

But seriously, even the simple Scrum framework, in the wrong hands or misunderstood, so that the enforced transparency is used to take control over the team, will lead to micromanagement and annoyed developers.

Ken Schwaber once suggested using a transition team to address the organizational change which is being demanded by the delivery units [Schwaber 2007], and that makes a lot of sense to me.

Let the agile delivery teams do their work and along the way they will quickly indicate the problem spots. Just pick up those indications and handle them with care. As managers, if you don´t find a way to show up for your people, to make clear that you care and are serious about agile, if you can not make it visible that you catch dysfunctions and find ways to solve problems, simply to deliver the organizational change that is needed, if you can´t do that, you can´t do agile. It is not enough to expect people to produce valuable software at the end of each iteration and the management does not do more than counting velocity points and staring on product burndown charts.

How would you expect the delivery people to build valuable things every two weeks, make everything transparent, while the management isn´t committed and organized to deliver necessary organizational change with a similar pulse?

To implement large scaling frameworks and not to use a transition team is introducing agile (by name, not by meaning) like a waterfall (yes, with a defined process model). Start with the transition team to scale agile and invent your mechanisms and solutions from what the delivery teams are revealing. Show that you care. See what works for your organization, be self-confident and do not copy others.

In the world of sports, when you start running, for example, it is not essential to have a pulse meter, fancy clothing and the like. Instead you only need a pair of running shoes and – of course – have fun and run regularly. When scaling agile in your organization, it´s the same. The core is to build and make things right. If you can do that in the small, with one team, think about growing larger. Learn while you are doing.

Supersize

Scaling agile beyond the first team is the first step of scaling. Is there an end? What size can you reach or want to achieve? How long does it take?

The general answer is, keep it as small as possible and, again, try to find the least solution that can work. Attacking the topic from the start as a scaling endeavor will not help you. Agile will scale itself when you allow it to honestly work at a team level.

Agile will scale itself when you allow it to honestly work at a team level.

Your organization will learn from such achievement and find a natural way to scale. Scaling is not the primary goal; it is a result of a curated successful agile implementation in the tiniest cells.

The more people are included, the more communication work is imposed on the people because communication effort will grow by powers of 2, and not linear.

Here is the simple math: Communication lines among people grow in terms of n(n-1) (with a team size of n). By this you come to 20 communication lines for a team size of 5, 30 lines for a team size of 6 and a team with nine people will have 72 lines that need to be maintained among senders and receivers in the team.

That´s the reason for not letting a team grow beyond ten people. If more people are needed to achieve things, split into teams with reduced dependencies between each other. The best concept to minimize dependencies, we know so far, is to have cross-functional teams where each team can deliver an entire feature that makes sense to a customer, end-to-end. You then have developers, front-end, back-end, QA, UX and so on in one team – in other words everyone who needs to be there to achieve to a result.

The other way around, having teams grouped by architectural components or skills, like front-end, back-end, UX and the like in separated teams, will increase dependencies and lead to teams blocking each other when delivering end-to-end features. No team alone can deliver, and the people will have to maintain not only the communication lines inside of their team but in addition to all people in other teams who are needed to deliver the feature.

Focus on this: have a team to be able to deliver done software by the end of each iteration, always doing the most valuable things first, and let them work together as a real team. From that point the people are in a self-carrying upwards movement. As managers you only need to move barriers out of their way, the rest they will go alone. Scaling before you reached that point will just let you scale up a mess.

Standup

Let´s assume you do daily standups with component- or skill-formed teams. Considering the purpose of a daily standup is to ensure the delivery of a feature by the end of your iteration and to unhide the necessary adjustments to reach that goal; usually, a daily standup with only the people who belong to a single architectural component doesn´t support you at all. You will find communication without direction and the impression of wasting time among the participants. This is not fruitful.

Instead, if all the people who deliver a feature are together from the start, a so-called cross-functional team, the standup supports collaboration and communication towards that goal of feature delivery, and the team can start to hunt features.

Feature and component matrix

Traditionally, most teams are organized by similar skills or technical components. My suggestion is not to throw this all up in the air and try to reorganize in feature teams. Instead, it can be a method to move on step by step. Try to see the entire thing as a fluent matrix structure. This is how it goes: Stick with the component teams and try to see them as a profession frame with people who keep their architectural component intact and maintain their specific professional skills. When you have a clear backlog with a straight line from your product strategy to the delivery order of your features, pick the first and most valuable feature and let the people select themselves by deciding who is needed to deliver it. Those people will be your first feature team. Then pick your next feature from the backlog and do the same again. You will be able to identify chunks of features that should go to one feature team or the other, but the important thing is, now you have two organizational dimensions – the established, that is grouped by components and skills, and the new one, which will support you to hunt for features. This is a start. Over time you identify patterns, see what is working, what not, and then you adjust.

Conway´s law

You may have heard about the essential idea pointed out by Melvin Conway, that you replicate the structure of your organization inside of your products [Conway 1968]. Simply, if you have a bloated, unfocused organization with unclear goals and responsibilities, your products will look the same. Instead, if you have a lean, focused organization with clear goals and responsibilities, again, this will be recognized in your products. For example, if two departments are responsible for developing a specific product, chances are, that the outcome will be made up of two components. If the two department heads cannot bear with each other, the interfaces of the two parts will not function well. In this case, you will find duplicated or missing attributes, performance issues, long durations to identify failures and so on. All that said, this doesn´t give you concrete advice how to structure your organization, but when people are getting aligned to develop a thing, keep Conway´s law in mind!

Principles

There is no precise recipe to follow. But you can use guiding principles that will support you on your journey to let an agile organization grow. I´m convinced that the ScALeD Principles point in the right direction. Believe in yourself and your organization, follow the principles instead of checklists. A checklist is useful for well-defined procedures that can be analyzed upfront (I´m using the term checklist as a drop in for "scaled agile framework"). When you reinvent your organization, a list will not help. Likely it will let you switch off your mind and make you repeat things other people have thought of.

In any way, embrace self-organization. This force of life will give your organization the power to survive in complex environments. In an enterprise context, self-organization needs to get a direction by setting constraints. These constraints have to address two preconditions for fruitful self-organization: competency and clarity [Marquet 2013].

Competency means the technical skills to do things on top of a craft. These skills need to be maintained and nurtured. You know, skills are bound to people.

Clarity means clarity in organizational goals and intent. Understand what brings value and follow the value.

Scaling agile is about emancipating people. Strive for clarity in goals and intent, let people grow their competencies and give them control to decide. Then agile is self-scaling. Focus on being agile at the team level. From there on you need to move barriers out of the way and growth will be self-carrying into the organization.

Some of the here stated positions are reflected in the article Was sich am einfachsten ändern lässt: Sie selbst! on entwickler.de.

References

- [Beedle and Schwaber 2002]

- K. Schwaber, M. Beedle, "Agile Software Development with Scrum," Pearson Prentice Hall, 2002

- [Cohn 2014]

- M. Cohn, "Introducing the LAFABLE Process for Scaling Agile," 2014, http://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com/blog/introducing-the-lafable-process-for-scaling-agile

- [Conway 1968]

- M. E. Conway, "How Do Committees Invent?," 1968, http://www.melconway.com/Home/Conways_Law.html

- [Jeffries 2015]

- R. Jeffries, "Do we really need another method?," 2015, http://ronjeffries.com/articles/2015-07-07-yet-another-method/

- [L.A.F.A.B.L.E]

- M. Cohn, "Large Agile Framework for Big, Lumbering Enterprises," 2014, http://www.lafable.com

- [Marquet 2013]

- L. D. Marquet, "Turn the Ship Around! A true story of turning followers into leaders.," Penguin, 2013

- [Mayer 2013]

- T. Mayer, "The People´s Scrum, Agile Ideas for Revolutionary Transformation," Dymaxicon, 2013

- [Wohland and Wiemeyer 2007]

- G. Wohland, M. Wiemeyer, "Denkwerkzeuge der Höchstleister, Wie dynamikrobuste Unternehmen Marktdruck erzeugen," Murmann Verlag, 2007

- [Schwaber 2007]

- K. Schwaber, "The Enterprise and Scrum," Microsoft Press, 2007